Local Indigenous Peoples

“The climate warmed. Wild grasses, flowers and trees took root in the land behind the huge rock. In time, their growing and dying made deep rich loam on which a magnificent forest grew. Into the forest came bear, deer, brightly colored birds, and .... a tribe.... The People of the Dawn.”

-Jean Craighead George

"To all Native Americans, the land did not belong to the people, people belonged to the land.” - Jean Craighead George

In Our Story

Indigenous Americans understand the world in its natural orders, rhythms and cycles of life and include animals and plants as well as other natural features in their everyday lives. They value harmony with and respect for nature, towards others, for the earth, the great spirit and for individual freedom.

All of this comes to mind when reading our story. Sam, and how he conducts himself in his chosen way of life, brings forward many of these ideals and qualities.

The Narragansett Tribe

"Asco wequássunnúmmis — hello — Kunoopeam ut aûke ut Nahahiganseck — welcome to the lands of the Narragansett" - Silvermoon Mars LaRose

Here in this place, you can still feel the timeless connection to nature, the seasons and ways of life that carved the generations, creating the first culture in Rhode Island.

This is where the Narragansett Tribe lived and thrived. And live and thrive.

It's a place they still call home, one of the few that remain, serving to help preserve their heritage and tell their story to those who come to hear it.

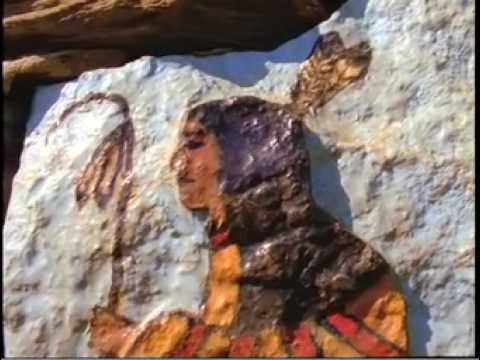

Left here is a photo of Princess Red Wing aka Mary E. Congdon, was a Narragansett and Wampanoag elder, historian, folklorist, and museum curator. She was an expert on American Indian history and culture, and she once addressed the United Nations.

cul·ture

/ˈkəlCHər/

the customs, arts, social institutions, and achievements of a particular nation, people, or other social group.

When Thawn Harris relates his stories in the form of fables, he is keeping alive an oral tradition that dates back centuries to pre-European settlement in the Americas.

One story, a creation story, involves a “sky daughter,” a turtle (“tunnapah”), and a muskrat. The three combined to help create “the people between the waters,” the Narragansett Indian Tribe.

“The oral tradition is how we passed along lessons through stories,” Harris said of the Narragansetts and other Native American tribes. "We want to grow and change while maintaining our culture and core traditions.

We incorporate new songs, dances, and games that focus on being thankful for what has been bestowed on us as blessings. We want to take time to see the blessings around us.”

In the Beginning

The Narragansett Tribe are the descendants of the aboriginal people of the State of Rhode Island. Archaeological evidence and the oral history of the Narragansett People establish their existence in this region more than 30,000 years ago.

This history transcends all written documentaries and is present upon the faces of rock formations and through oral history.

The Narragansett people are the Algonquian American Indian tribe indigenous to Rhode Island. Their name is said to mean “People of the Small Point.”

Archaeological evidence and the tribe’s oral history says that the people occupied Rhode Island for thousands of years before Europeans arrived.

Relationship to Nature

American Indigenous cultures respect nature above all else. ... Native Americans operate under the conviction that all objects and elements of the earth—both living and nonliving—have an individual spirit that is part of the greater soul of the universe.

Historically, the Native Americans used natural resources in every aspect of their lives. They used animal skins (deerskin) as clothing. Shelter was made from the material around them (saplings, leaves, small branches, animal fur). Native peoples of the past farmed, hunted, and fished.

Indigenous Americans have long had an immediate and enduring relationship with their physical environments. Most lived in relatively small units close to the earth, cognizant of its rhythms and resources.

They defined themselves by the land, by the sacred spaces that bounded and shaped their world. They recognized a unity in their physical and spiritual universes, the union between the natural and supernatural. Their origin cycle, oral traditions, and cosmologies connected them with all animate and inanimate beings, past and present.

This is a photo of Pine Tree, a Medicine Man of the Narragansett Tribe.

“Our beliefs, songs, dances, and stories all come from the natural world. We have to know the characteristics of animals, plants; they provide food, medicine, and technology. A ‘super plant’ has all three of those characteristics. If you’re not connected to the land and food, how are you going to continue to express yourself?”

-Cassius Spears

Indigenous Americans manage this world's bounty and diversity based on years of accumulated wisdom and the trial and error of previous generations. They acknowledge the earth's power and the reciprocal obligation between hunter and hunted. They act to appease the spirits who endowed the world.

Indigenous peoples celebrate the earth's annual rebirth and offered thanks for her first fruits. They ritually prepare animals they have killed, agricultural fields they tend, and the vegetal and mineral materials they process.

Seasonal Homes

The early Indigenous American population in New England lived in different parts of the region for different purposes at different times of the year, mostly in scattered villages.

These villages were located in proximity to the bay in places like the recently discovered Salt Pond coastal village site in Narragansett, along the coves and inlets near Wickford, Hamilton, Rome Point and Quidnessett.

They could also be found in the riverine margin areas in Charlestown and South Kingstown, near Devils Foot Rock in North Kingstown and out in the farming regions of Slocum.

Historically, tribal members had two homes; a winter home and a summer home.

Winter Homes

Their winter homes were longhouses in which up to 20 families would live in over the cold months.

There is not much evidence for large permanent settlements in this area, except at one site called RI 110, which is located northeast of Point Judith Pond. Here, archaeologists discovered evidence for about 20 structures that varied in shape and size, and the interior of the largest was 70 square meters.

This large structure most likely served a communal function where people would gather for different purpose like ceremonies or meetings. Archaeologists estimate that approximately 60 people lived in this community, but the population could have been as high as 100 or 150.

Bottom photo here is the Narragansett Longhouse of today.

Summer Homes

During the summer, the tribe would move to the shore and construct Wigwams or Wetus, temporary shelter made of bark on the outside and woven mats on the inside.

They had vertical sides and were either round or oblong. They were built with small poles fixed in the ground, bent and fastened together with cord. The base pole structure would be covered with reeds, bark, or mats. A smoke-hole would be left at the top to allow the smoke from the inside fire to vent up and out.

Thanksgiving

Loren Spears, director of the Tomaquag Museum in Exeter, RI said the Narragansett have thirteen thanksgivings, one for each new moon of the year.

"We went by the lunar calendar, and at each moon there was a lunar harvest. We sometimes today interchange the term ‘moon’ with ‘thanksgiving.’ So the moon is the timing and the thanksgiving is the ceremony," Spears said.

Thanksgivings often coincide with the food being harvested or gathered at any given time throughout the year, they include thanksgivings for strawberries, green corn, and fish among others.

Silvermoon LaRose explains that giving thanks is a daily virtue for the Narragansett tribe. And this about the 13 thanksgivings, or “13 Moons on Turtle’s Back"

“For each of the 13 squares on the turtle’s back, which follow the moon cycles, we have ceremony,” said LaRose. “We reflect on our local ecosystem, we give thanks for all of the gifts from land and waters. These are practices that we still hold dear today. It’s the way we continue our culture.”

Specialized Knowledge and Skills

Specialized knowledge includes a range of factual, theoretical and practical knowledge, as well as competencies and skills particular areas.

Exemplary Warriors

When the colonists arrived in New England in the early 17th century, the Narragansett were some of the most powerful Peoples in the southeastern New England region.

Members of the tribe were well known for their prowess as warriors, offering protection to smaller tribes (such as the Niantic, Wampanoag and Manisseans) who in turn paid tribute to them.

In warfare, the Narragansett sought captives and tribute from their defeated foes, while the European style of warfare aimed to destroy the enemy.

This skill as warriors was historically true and continued through time...

“Per capita, native people have served more in the armed forces than any other nationality of people,” she said. “Native people are proud of their service, and we have generations of people who have served in every conflict since the Revolutionary War. So we have a long military history and a lot of veterans within our community.”

- Silvermoon Mars LaRose

Hunting

Narragansett men did most of the hunting. They shot deer, turkeys, and small game. When they killed a deer they ate the heart, or buried it and so returned it to the land. Narragansetts used deer not just for their meat.

They then used the bones and antlers to make awls, jewelry, scrapers, hoes, and needles, the hoof for glue and rattles, and the hide for clothing, quivers, blankets, and pouches.

Firsthand Info

Interviewer Tom Burns talked with Lloyd Wilcox, the Narragansett medicine man, and his wife, Alberta, who also grew up in a traditional Narragansett family and was a nurse. Lloyd built stone walls in traditional styles in the region, also documented in the collection. Both Lloyd and Alberta grew up with hunting, fishing, and traditional farming, and then continued these traditions in their own family. In Part 1 of the interview in the player below, the couple talked about hunting and fishing, using every part of the animal, smoking fish, preparing and eating skunk, gathering wild foods, crops they raised, and family stories. This interview helps to show the extent that some of the Narragansett people had succeeded in maintaining their traditional ways in the 20th century.

Fishing/Gathering

Food sources for people living on islands or by shores might have been more diverse, which enabled them to have a rich diet without being forced to practice agriculture.

On Block Island, for instance, intensive use of a wide variety of flora (plants) and fauna (animals) was taking place on a year-round basis as early as 3000 years ago, some 1000 years earlier than on the mainland coast.

At Harbor Pond Site on the island, archaeologists found artifacts including stone arrow or spear points, scraping implements, and fishing weights used in the hunting of land or perhaps marine mammals, processing and consumption of shellfish, and fishing.

There seemed to be as many ways to fish as there were kinds of fish.

The fish hook persisted from the Early Archaic days, simple and effective.

Spearing fish was popular with spears bearing points of bone wedged into the shaft.

Spring also brought spawning runs. A river outlet could be fenced off with branches that the fish could swim right through to the spawning grounds but on the return, the current would force them against the barrier.

Summertime brought low water to streams. A stone wall in the shape of a funnel, was built at a drop in the streambed. The rapids, made moreso by the narrowing, tumbled fish onto a sieve of sticks.

Nets were also used made of hemp and other fibers, especially from the linden tree. Purse nets were crafted from a split of a stick lashed to a handle.

“We are a coastal people. Our entire culture is built off of the waterways, and we have no coastal property,” LaRose said. “What does that mean as a community when we’re trying to continue certain practices and teach future generations if we don’t have access?”

Dug-out Canoes

Indigenous Americans used pine, poplar, and maple trees to create canoes and would burn and then dig out large canoes from trees which could hold up to forty men. They used them for transportation and for ocean fishing trips.

Again... In Our Story

Sam remembers that Native Americans carved out their canoes by using fire to create a dugout. This give him the idea in how to more efficiently dig out the big hemlock to use as his home.

He carries a burning stick to the hemlock tree and starts a fire in the opening. Since Sam is always thinking, he also realized that he should have water on hand in case of an emergency with the fire. He discovers a pool of water, which also has a lot of crayfish living in it that he can eat, but realizes that he has no bucket to transport the water. Sam settles on using dirt to put out the fire, should there be a mishap with using fire to hollow out the tree.

Tall white pines provided the basic shape, and it's size determined the finished length of the canoe. The trees were felled by fire, which was at the base and fed with dry moss and wood chips, burned close to the roots. A stone ax knocked away the charcoal as it went.

Limbs were burned off and the bark was stripped free. The log was raised on supports and gradually burned, chipped and scraped into shape. Hot pebbles gave added heat penetration.

As the hollowing progressed, the charcoal was removed with scrapers. Earlier cultures probably used the gouge and adz. Along the coast, quahog shells were ready made scrapers.

When the fire moved to briskly, water was used to protect the edges.

The bow and stern were blunt.

Masonry/Stonework

Early on, Narragansett tribal people were employed by the earliest settlers of Rhode Island to make stone fences. As we discover more and more remarkable dry stone work in the remaining wilderness, it becomes quite apparent why the English paid them to do such work -- it was most likely a skill they already possessed. Later they were enslaved and forced to do the same work, but without the benefit of pay.

The amazing examples found in cairns all over the state, from the Tomaquag site in Hopkinton, to the Queen's Cairns in Exeter, to Parker Woodland, and many more -- few can deny that building these structures took time and hard work. A testament to the workmanship is how these structures have survived hundreds of harsh New England winters, various hurricanes, and countless nor'easters.

The Francis C. Carter Preserve in Charlestown, RI is only a few miles from present-day Narragansett Tribal Lands. On display there is an undeniable history of Narragansett masonry.

An array of eras is evidenced by the many features, from ancient stone rows, cairns, and split-wedged rocks, to 18th and 19th century drilling techniques. This site, better than any other in Rhode Island, tells the story of the stone masons of the Narragansett Tribe.

The Narragansett tribal stone masons who, over the last four hundred years, have built many stone walls that wind picturesquely through the woods of southern New England.

In the photo right is Russel Spears, one of South County's master stone masons, and below left is Lloyd Wilcox in front of one of his walls.

Stone masonry continues to be a traditional craft of the Narragansetts. For example, Narragansett masons were employed to build the stone walls that criss-cross the Pequot Reservation, home of Foxwoods Casino. The Narragansett Indian Church was burned to the ground and rebuilt twice using granite shaped by the hands of Narragansett masons. Present-day Narragansetts are able to trace the craft back several generations in their families. The skills are handed down from grandfathers, fathers, and uncles.

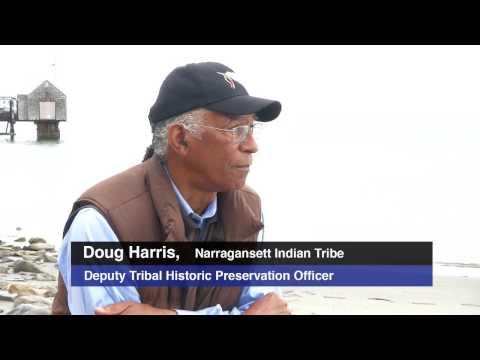

RI PBS Documentaries

Stories in Stone is an engaging film about the Narragansett tribal stone masons who, over the last four hundred years, have built many stone walls that wind picturesquely through the woods of southern New England. Interspersing footage that elegantly captures the beauty of the walls with interviews with tribal elders and members of two prominent Narragansett mason families, producers / directors / writers Marc Levitt and Lilach Dekel weave a story that is both poetic and inspirational. Filmed in both video and film, Stories in Stone uses scenic footage and original music to express both the traditional and contemporary aspects of this craft. With no central narrator, Stories in Stone allows the Narragansett to tell their own story.

More..

Woven in Time: The Narragansett Salt Pond Preserve, is a documentary about the only surviving and recently preserved pre-contact (1100-1400) Native American village on the New England coast. A film of extraordinary beauty and poetry, Woven in Time is a story of 'place' - how land and spirit are interwoven and how uncovering this village could lead to a shared stewardship for this beautiful and bountiful territory of marshes, ponds, oceans and forests.

This land, used for dirt biking and adjacent to a suburban housing development and shopping center, is on a pond in Point Judith, Narragansett, where the Narragansett people place their origins story. In the 1980s, archaeologists unearthed the remains of a centuries old village that managed to survive 'untouched' in a highly built section of the Rhode Island coast. The parcel then became the center of an almost 30-year battle between the right of property ownership and the social and cultural importance of preserving one of the most important archaeological sites on the East Coast of the United State

Gardening/Cultivation of Corn/Agriculture

Excavations at sites on the Pettaquamscutt River (AD 850) and Narragansett Bay (AD 250) had evidence for carbonized wild rice and sunflower seeds, suggesting that non-domesticated plants and seeds were being processed, even when corn wasn’t.

At the end of this period, when Europeans wrote about New England around AD 1500, they talked about corn and beans being part of the Native Peoples’ diets, which shows us that agricultural production slowly became an essential part of Native Peoples’ lives.

You can call it what you will – maize, hard-shell corn or cornmeal corn – but this once wild member of the grass family, native to central Mexico, is one of the most important things to come out of the New World.

Originally, its seed head, or cob, of which there was only one to a plant, was about an inch long. After countless generations of careful artificial selection by the indigenous people of the Americas, which occurred across centuries, this little grass with its energy-packed seed head became one of a number of critical factors impacting cultural success in the New World.

Those who possessed it, and understood the intricacies of its cultivation, were able to add agriculture to their survival repertoire a mixed bundle of food procurement strategies that led to a better chance of both individual and community success.

These folks were agricultural geniuses who took a simple grass plant and modified it across time into a nation builder.

The Narragansett people here in South County fully realized how important maize was to their health and well-being. Indeed, its story was an integral part of their nature-based belief system.

Every Narragansett child knew the legend of “the Gift” – how their creator spirit, Cautantowwit, sent them maize in the beak of his messenger bird, the crow.

It was the reason that young Narragansett children guarded the fields and only shooed the crows away; no Narragansett would ever kill a crow.

Three Sisters

The Narragansett people accepted “the Gift” and used sustainable strategies to encourage its growth and maintain its yield. This they called the “Three Sisters.”

They planted maize in a mound, a few kernels along with a small fish, now called an alewife, for fertilizer. Maize was the first sister and as she grew, the Narragansett planted the second, a hard shelled-bean, which they trained to climb up the trellis-like corn stalk. At that same time they planted the third sister, one of a variety of squash, similar to today’s acorn squash, pumpkins and gourds, which they trained to grow around the mound; the squash’s big leaves shading the mound to minimize evaporation.

The selection of these specific three crops was well thought out and based upon generations of trial and error.

All three of these foodstuffs were protected from mold, insects and varmints by a hard shell. In this time long before refrigeration, these foods could be stored in specially designed lined pits in the ground and last throughout the winter, guaranteeing nutritional meals for the tribe almost year round.

And this symbiotic planting strategy worked perfectly in the environment that was southern New England. The crops did well, and in turn the Narragansett thrived.

Think about it; these people were the architects of a complex agricultural strategy that brought them success and a good life. A child born into this world benefited from the success of this planting strategy.

The Narragansett settled for the most part in areas specifically chosen to help assure this success. These places were on the margins between two ecosystems; — one water-based one, along a river or large inland freshwater body or along the various protected coves and inlets of Narragansett Bay, the other a forest edge, a place suited for planting the Three Sisters.

Food, both fin and shell fish, could be reaped from the river, pond or bay and, supplemented by the Three Sisters and other gathered plant products of field and forest, helped fill the nutritional needs of the tribe members.

Each season the planting areas were cleared using a very carefully monitored slow burn. It involved just enough smoldering to turn vegetative matter into fertilizer for soil replenishment; too hot a fire scorched the soil and ruined it for planting.

The Narragansett knew all this, just as they knew the cycle of the alewives, it was critical; It was agriculture.

Petaquamscutt Community Garden

Today the Petaquamscutt Community Garden is up and running, cultivating, regenerating and restoring the natural balance of Mother Earth.

Wayne Everett, of the Narragansett Tribe, along with other members and Elders, are committed to planting seeds and bridging communities while healing and strengthening relationships and carrying on traditions.

This nonprofit organization is wonderfully and bountifully growing and serving the community.

Pettaquamscutt Community Gardens is an Indigenous lead agency focused on Environmental Justice through Agriculture, and Restoring the Natural Law and Balance of Mother Earth, living in Harmony with the Creator’s Natural Elements, and promoting Food Sovereignty, Health and Wellness through Community Involvement, Culture, youth and adult Educational Programs, using Ancestral knowledge and Traditional Methods to Cultivate and Regenerate the lands. While creating Socio-Economic sustainability for our Indigenous Community, and those most Impacted.

Wampum

Long before the arrival of European settlers, the Narragansett were crafting beautiful artwork that expressed who they were as a people – a custom they have passed down for thousands of years. This includes many different kinds of skilled craftmanship from painting and ceramics to meticulous beadwork and jewelry making.

Importantly also Wampum, or the beads made from quahog and whelk shells.

The quahog shell’s most significant contribution is the tradition of wampum, or cylindrical beads, that when strung together are worn or displayed for special ceremonies and celebrations “honoring leaders and warriors for their contributions or significance in the community.”

Wampumpeag means “white beads” in the Algonquian language spoken by the Narragansett tribe, while wampum belts were used for visual storytelling. “The mix of the purple and the white from the shells was used to tell a story, to make record of historical events and things that were happening within our tribal communities, so the way the two were fashioned together had meaning,” According to Silvermoon LaRose.

Wampum was sacred to the Narragansett – to make it required a highly developed and time-consuming skill, and to obtain it, you had to earn the right to have it from your community.

“When you exchanged wampum it was the highest honor you could give to somebody else,” LaRose said.

Loren Spears says wampum signified truth and beauty in its creation, which is why “runners would travel from one village to another with these strands of beads to signify the truth of the message.”

“During trade and treaty agreements, they wanted to make sure that everybody meant what they were saying, that everyone will hold true to their word. Wampum was exchanged as a sign that all were in agreement, and the agreements were respected and all participants were honored.”

“American history has taught us, for years, that wampum was native money,” LaRose said. “But we didn’t have the concept of money, in that an object could hold worth in and of itself, and if you amassed much of that, you amassed wealth and you could buy what you wanted.”

"Wampum had always been used ceremonially, but (Europans made the idea of) it became synonymous with money. Lengths of beads were called stropes and length determined the value. The purple, which came from quahog shells, were worth twice as much as the white, which came from whelk, all of which was abundantly available in the bays from Long Island on up through New England."

Tribal member Annawon Weeden explained that “It is insulting when somebody reduces wampum to money.

You can literally hold beads that your great, great, great grandfather made. You cannot do that with the (U.S.) Constitution or the Declaration of Independence.

I try to incorporate mind, body, and spirit meanings into my (art) work.”

Wampum is still made and cherished today and can be found on display in the Tomaquag Museum’s bead exhibit.

The Purple Shell

THE PURPLE SHELL, An authentic Eastern Native trading post featuring Wampum, native crafted jewelry, along with many other hand crafted items based around the ocean and Eastern Native Life. 401-364-8088

It is located in Charlestown at The Fantastic Umbrella Factory.

More

“Our cultures, our very being as a people, are what makes each ethnicity different from one another. Those differences, whether recognized through language, foods, arts, clothing, etc., must be appreciated to better understand one another,” said Tribal Councilor Randy Noka, who sits on the tribe’s Economic Development Regulatory Commission. “The Native American culture is as vibrant and strong as ever.”

Tomaquag Museum

The Tomaquag Museum, located in Exeter, is the state’s only museum dedicated to sharing Indigenous culture, history and art that connects to current Native American issues. It was founded in 1958 by anthropologist Eva Butler with Mary E. Glasko, also known as Princess Red Wing of the Narragansett/Pokanoket-Wampanoag Tribe, who hoped to educate others with her cultural knowledge.

The museum showcases an array of Indigenous collections from the tribal communities of southern New England, including the Narragansett tribe. One of these artifacts is the quahog, a Rhode Island favorite to both shell and eat. But quahogs also play a sacred role in the diet and culture of the Narragansett tribe, says Lorén Spears, executive director of the Tomaquag Museum.

"The mission of this place has always been to create a dialogue of the times," said Kate April, treasurer for the Tomaquag Indian Memorial Museum, now in its 51st year. "So often we're preaching to the choir, but we're trying to reach out to those who don't really know the history. Through our programs and exhibitions, we're presenting the Narragansett people as a viable culture, making sure that Rhode Islanders understand that they were the indigenous people."

The museum, which is affiliated with the Nuweetooun School next door, hosts a collection of American Indian artifacts from across the continent. Highlights include a diverse collection of southern New England ash splint baskets with stamped and painted designs, a craft that was a specialty of the Northeastern tribes, as well as a large collection of corn husk dolls and other historical and archeological items.

Tomaquag - which is a Narragansett word for "beaver," symbolizing a homemaker and an industrious worker that builds and changes its environment - relies heavily on volunteers and grant donations.

Through one recent grant, the museum is undergoing a collections assessment and architectural study, the first stage in what is hoped to be an extensive redesign of space and storage.

The Narragansett People have seen many changes in their lands; however, their traditional culture has been passed down from generation to generation and is even stronger today. Narragansett Indian men and women have fought with honor in every war starting with the United States revolution. Tribal members have careers in every profession including; doctors, lawyers, teachers, artists, as well as fisherman, lobsterman, cooks, and masons.

The Tribe has greatly expanded its administrative capability. Policies and procedures have been implemented to protect and preserve its land, water and cultural resources and promote the welfare of Tribal members. The education, family circle, traditional ceremonies, and Narragansett language are important aspects of the Narragansett Indian Tribe’s culture and daily lives. Tribal monthly meetings and other special, traditional gatherings take place at the Four Winds Community Center, on Route 2 in Charlestown, RI.